The Greater Good

A defense of the humane society

It’s been half a year since I’ve written a blog post: In what spare time I’ve had for writing, I’ve been wrestling with the next chapter of my book, which covers what I also intended to be the next installment of this blog, focusing on the rise of illiberal authoritarians.

I found this a surprisingly difficult task, both in trying to order and articulate my argument intelligibly, and because its importance and centrality to today’s events only seemed to grow with every passing week and brand new development. After 12 months of struggling with this particular chapter (in contrast, I’ve pretty much finished the next chapter in a single weekend), I’m finally done with it and want to share with you a condensed version of the argument.

Where I had left off in writing to you, I had suggested, in The World Turned Upside Down, that there were four “different constituencies of the Trumpist movement,” and discussed the first of these, the fundamentalist nostalgists, in my last post, Decline and Fall. The next installment, the discussion of illiberal authoritarians, drawn from the same book chapter as this post, is going to appear separately online in The Hedgehog Review (which, by the way, I consider by far the best publication of any sort out there these days); I’ll send a link to that piece when it appears.

But it’s not enough, in the current worldwide assault on liberalism, simply to critique il-liberalism: Both left and right offer longstanding critiques of liberalism – of individual freedom as a threat to social cohesion and order, of free societies as inadequate to the challenges of a nasty world, of economic freedom as a chimera that only leads to the subjugation by the Haves of the Have-nots, and of humane values as atomistic and reductionist and thus antithetical to any higher value – that need affirmatively to be addressed.

In the forthcoming Hedgehog piece, I discuss the argument, currently both in vogue and in power on the right, that empathy for others is actually a liberal plot to destroy civilization. The more traditional, anti-liberal critique was recently well encapsulated by the conservative columnist, David Brooks: that “the Enlightenment took away the primacy of the community and replaced it with the primacy of the autonomous individual,” producing a “moral vacuum” because “devotion to that common order [became] voluntary.” (A not dissimilar critique comes from a sympathetic source in Anton Barba-Kay’s recent piece in Hedgehog: “The problem with liberalism as an ideology is not that it is false but that it has ceased to present itself as a political and moral vision of the good among others.”)

This issue of morality, about which liberals generally try to avoid being explicit, is in fact crucial. The root difference historically between liberals and illiberals lies in their respective beliefs about the fundamental human condition: whether people are capable of finding and acting upon moral standards on their own, without these being imposed upon them, and, ultimately, whether an order can be “moral” without being imposed. I sure hope so – and am willing to believe so.

This post, and my book, are about how it might be so: about how we can and should re-conceptualize liberalism for the 21st Century – amidst today’s extreme right-wing rejection of empathy for others and the left’s rejection of the individual – around the principle that, as both a moral and a practical starting point, all of us should place the interests of others ahead of our own.

SHARING VALUES

As I’ve written previously, today’s material environment – our digital technological superstructure – fundamentally undermines not just all existing institutions but also all shared “authority” and objective reality, producing social isolation in our own self-contained realities.

In a world where we can create our own facts and our own realities, the only way we can then “reason together” – let alone act together – is if we can start from shared values. Can we actually do so?

In fact, our values are today the one thing we can talk about together. A large majority of Americans agree in poll after poll on most issues. The more you delve deeper than specific issue positions, into basic values, the broader the consensus you find across virtually all Americans.

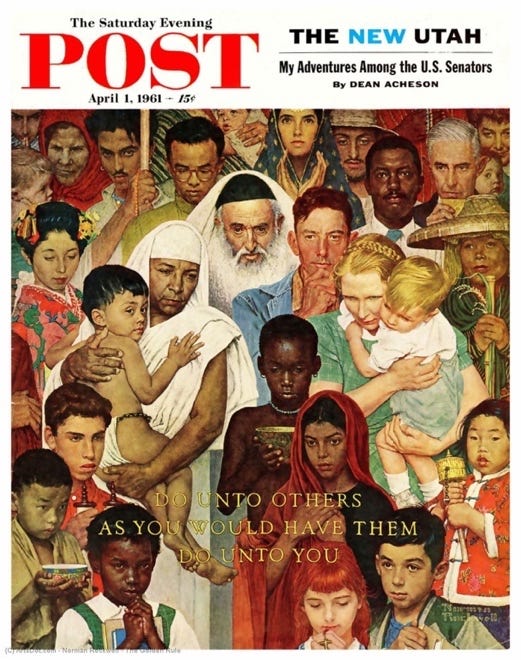

The world’s religions have (for humans) a shocking uniformity of belief as to basic values. In the main, all religious systems are constructed on the belief that life – at least, human life – is sacred, creating an essential equality amongst all imbued with it, a foundation upon which all other moral principles are built. Virtually every religion therefore places some variant of “the Golden Rule” at its center (see Leviticus 19:18 and Matthew 7:12, for starters, but also the Sayings of the Prophet Mohhamed and The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa).

While many agree with Dostoyevsky that one cannot in fact establish morality without religion – i.e., without a belief that ethical norms have been handed down by a higher power who must be obeyed – essentially the same fundamental ethical principle as the Golden Rule was derived in modern philosophy through pure logic by Immanuel Kant in his so-called “Categorical Imperative”: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law” – or, in more modern terms, Only do something if the world could still function with everybody doing the same thing as you.

In fact, a sense of what the right and good require has been demonstrated in psychological studies to be innate in most human beings. So, we actually do start largely with basic agreement on values. This turns out to be true not just of humans. Animals – from dogs to primates – have been shown to exhibit the same basic moral insight: Treat me decently as long as I treat you the same. Which takes us to game theory.

Game theorists have identified dozens of standard “game” situations that recur daily in the real world, and which can be analyzed rigorously. Many of these are so commonplace, and others so famous, that they have been given snappy names, the most famous of which is the “Prisoner’s Dilemma.” The Prisoner’s Dilemma involves two prisoners arrested for a crime, held separately, and – as is often the case in real life – told that, if they confess and implicate the other, they’ll get a lighter sentence. It’s in the interest of both to “cooperate” with each other and thus stay silent. But if one dimes out the other who then remains silent, the prosecutor will throw the book at the one who doesn’t “defect.” As a result, both defect and wind up with significant prison time instead of both getting off scot free. And that’s what makes it a dilemma: By acting in their own interests, they deliver themselves, both individually and jointly, suboptimal outcomes.

One of the most famous “experiments” in game theory was a series of computerized “tournaments” run by a University of Michigan researcher named Robert Axelrod in 1980. A number of leading game theorists, social scientists and economists were invited to participate. Rather than “playing” the Prisoner’s Dilemma against each other, they submitted proposed strategies for playing the game – such as “behave randomly,” or “always defect.”

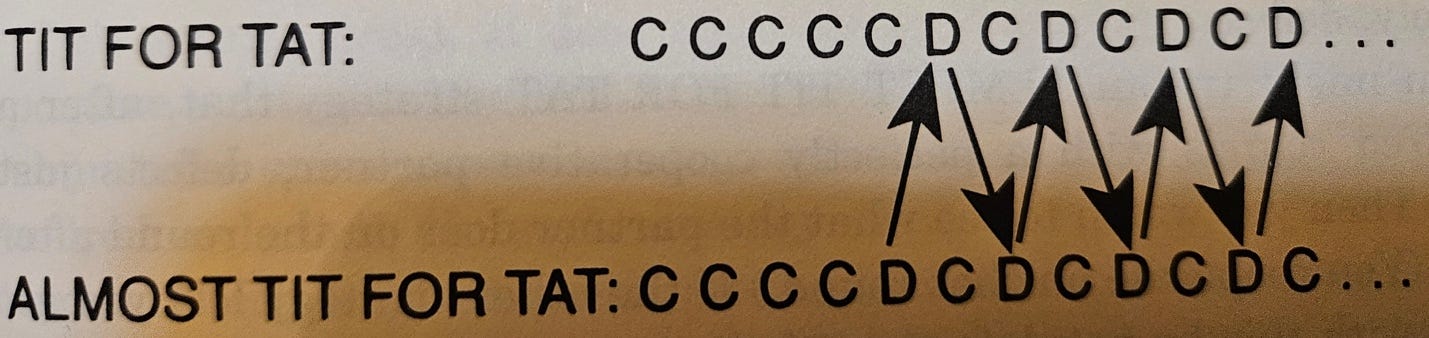

The winner of the first tournament, a program called “Tit-For-Tat” (or “TFT”), was simple: Cooperate on the first encounter, and then respond in kind thereafter to whatever the opponent does. As long as both players cooperate, cooperation continues – and both players do better than in any other scenario.

TFT has stood the test of time and, while it has its problems, it is widely regarded as the most effective strategy in Prisoner’s Dilemmas and other situations involving – like most of life’s interactions – reiterated one-on-one encounters. It is also what is known as “evolutionarily stable”: a behavior that persists when nearly all members of the population behave this way because no alternate behavior can displace it.

THE GREATER GOOD

In the game-theory games that – like much of real-world economic and social interactions – produce “dilemmas” (such as the Prisoner’s Dilemma), each player generally has a choice between his or her own, immediate, maximized gain or an outcome that is better for others or even, sometimes, themselves in the long run. Each of those presents a potential good greater than that individual’s immediate own.

How we each might advance the greater good is a question we all consider individually. What concerns all of us collectively, however, is: How might we design our society and its governance systems so as best to advance the greater good?

That requires more than simply value-maximizing calculations that economists define as optimal efficiency – and which often don’t even produce that – and it requires going beyond tit-for-tat. Acting out a concept of the greater good – something greater than oneself – requires putting the needs of others first in calculating one’s next “move”: In game theory terms, it means never being the defector and, instead, always cooperating.

Put another way, to pursue the greater good we need to reverse the notion of universality in Kant’s “categorical imperative,” which looks at the world as if through a telescope backwards, from the wide open end down the tube to yourself, the onlooker: What if the entire universe behaved as I do?

Instead, let’s look through the small end of the telescope that lies solely in our hands and choose our actions based on how best to contribute to that universe we see at the other, wider end – which encompasses anything but, and without reference to, ourselves, focusing instead on what’s at that other end, not our own: to paraphrase John F. Kennedy, asking not in any instance what others can do for you, but what you can do for everyone else.

This may sound unnecessarily or unrealistically self-effacing. I don’t believe it is. I will note a simple linguistic truth which belies a deeper metaphysical one: Our word “to want,” which we generally use to express something we desire, actually at root refers to lacking something – as in the nursery rhyme concerning “the want of a nail” causing, ultimately, the loss of a kingdom. The term dates back to Old Norse in the 12th century in that original sense, and didn’t come to mean needing or desiring until over a half-millennium later. In that basic sense, then, if you want nothing, you have everything. I work hard at wanting nothing; I don’t always succeed, but I find that when I do, I am by definition happier and fulfilled because I already have everything. It then becomes much easier – and, actually, far more rewarding – to focus solely on meeting the needs of others.

This may seem to fly in the face of the traditional view that every individual has the right to put his or her own interests before all others. But I’m not arguing against the idea of self-interest as a right, only against the idea that it’s the right thing. Individuals can always put themselves first, but not only would I argue that this is morally wrong: Even more so, as a practical matter, everyone pursuing their own self-interest leads to grid-lock and social dilemmas that are counterproductive for all. Each individual’s deference to others is the best, if not only, way to build a society that protects every individual’s interests. Very simply, if everyone were always to heed the ancient sage Hillel’s famous warning – “if I am only for myself, what am I?” – no-one would need to worry about Hillel’s set-up question, “If I’m not for myself, who will be?”

We don’t need here to settle the eternal debate between utilitarianism (weighing one person’s benefit against another’s) and ontology (a fixed rule as to what’s always right). We can’t here answer definitively, with just this one simple rule, what is the right thing in all instances. But we can answer definitively what is the wrong thing: To use game theory terms, it is always wrong to defect – to pursue self-interest over “the greater good.”

THE HUMANE SOCIETY

What do these values mean for political structures?

Let us think, for a moment, of “the state” being – or, at least being led and personified by – a single person (as has, in fact, historically been generally the case, and is certainly what authoritarians envision). This state, then, even though representing everyone, must face the same constraint as everyone else to respect the rights of the individual and put these first. The basic claim to human dignity and freedom in the face of the state doesn’t arise, then, from my right – as much as anyone else’s – to do as I please and get what I want; rather, it arises from my (and everyone else’s, including any would-be despot’s) duty to allow and enable others to do as they please and get what they want. It is altruism and empathy by each for each that create, and in fact compel, freedom and fulfillment for all. As Abraham Lincoln famously put it, government of the people that is necessarily also by and for the people.

A liberal and humane society means that, in yielding to others, we are recognizing the legitimacy of each individual’s claims, at least up to the point where they intrude on those of another (other than oneself). That means that there must be some irreducible personal zone in which each person’s right must be recognized as sovereign and supreme. Governments therefore cannot justify suppression of individual rights beyond at least a certain minimum even to achieve legitimate state purposes – and can only justify intrusion on individual rights at all when democratically authorized.

Similarly, every individual endowed with these basic rights also carries an obligation to recognize the rights of others. This is where we start getting into the difference between “can” and “should” – and between what might be morally wrong and what can properly be made unlawful. (This distinction was explored at length, and with great eloquence, by John Fletcher Moulton, in a lecture published posthumously, “Law and Manners,” (1942).) Let’s illustrate this with a trivial but concrete example: I have just as much right as you and everyone else in the crowd to push through the narrow entrance to the stadium where our favorite band is playing a concert in just a few minutes – but that doesn’t mean I should push my way in front of you. While there is a wide range of behavior I can undertake in a free society, there is plenty I should not in a decent society, out of deference to others. But that is a matter for private morality, and a limit on the collective, or, “the state,” to compel otherwise.

As Cass Sunstein has summarized the liberal project, the foundational work of John Stuart Mill “insists on a link between a commitment to liberty and a particular conception of equality, which can be seen as a kind of anti-caste principle: If some people are subjected to the will of others, we have a violation of liberal ideals. … Liberals are committed to individual dignity.” This is indeed how liberalism traditionally has been defined: One starts with a principle of individual dignity and arrives at further principles, first, of political freedom and, then, equality. Perhaps not coincidentally, this logical progression also describes the historical evolution of modern liberalism, from its 18th and 19th Century libertarian roots to 20th Century New Deal and Great Society pro-active government, and finally to identity-centric 21st Century “progressivism.”

But this underlying premise – the firstness of the Individual – is what has drawn the scorn and rejection of both reactionaries and radicals, right and left. Instead, we travel here via a different path, grounding the sacredness of the Individual in the firstness of others rather than of self. If we build the idea of a humane society, and the protection of all individuals against domination and extraction by others, out of empathy for others – rather than, in reverse, deriving empathy from liberalism – we might rescue historical liberalism from the challenges and criticisms it faces today from both extremes: that it is spiritually hollow and materialistic, that it is antisocial and egoistic, that it is necessarily confrontational and unstable.

THE SUCCESSFUL SOCIETY

Can – as Abraham Lincoln asked – a society “so conceived and so dedicated,” one where all put others first, actually “long endure”?

The current right-wing argument that empathy for others is the cause of “civilizational suicide” is in fact old news: “Social Darwinists” have long used Darwin’s theory of evolution to argue for the dominance of the strong (or wealthy) over the weak (or poor) and against empathy as a matter of policy. This interpretation of natural selection has recurred repeatedly over the intervening years – most recently, in the work of evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, who coined the term “the selfish gene.” Dawkins advanced a theory he deemed descriptively correct, not morally prescriptive, framing what has long been the prevailing view this way: “Much as we might wish to believe otherwise, universal love and welfare of the species as a whole are concepts that simply do not make evolutionary sense.”

Darwin himself, however, rejected this interpretation of his work and in fact argued that self-sacrificing in favor of others served valid evolutionary needs and species that embodied this trait were more likely as a whole to survive. This insight was taken up in the latter half of the 20th Century by other researchers, starting with William D. Hamilton and George Price, who began giving such qualitative theories a quantitative grounding, developing mathematical models demonstrating that altruistic behavior could extend beneficially to other family members, and even – among social animals – to members of one’s reciprocating group. Robert Trivers enlarged on this idea with a theory of “reciprocal altruism” – that long-lived species who live interdependently, and therefore share in the care of the next generation and develop knowledge of each other’s personalities and “reputations” for trustworthiness and reciprocity, evolve egalitarian organizations and do better than those who simply go it alone.

Further evidence emerged that reciprocity doesn’t derive from, or serve, simply biological relationships: In fact, perhaps the most prominent evolutionary biologist of our day, E.O. Wilson, who developed the idea of “kin selection” – in other words, that natural selection’s “winners” are those related to you, not necessarily you – changed his mind later in his career to champion generalized cooperation amongst individuals as the key to evolutionary success of social species. He even developed a more rigorous mathematical model of evolution that incorporated and balanced both kinship relationships and more general social cooperation.

The major reason for the success of social species – like humans – in this view is the building of communities that can be defended, and in which lives can be lived, reproduction can occur, and offspring can be raised, generation after generation. Anthropologists studying still-extant hunter-gatherer societies found such altruism even in groups where children move to other communities, so that group members tend more to be simply friends rather than relatives. Looking out for others thus serves evolutionary purposes other than the simple transmission of genes: It helps groups, and each of their members, to survive and thrive.

In sum, in a war of all against all, those who defect and pray off the kindness of strangers may in fact be the ones who succeed. But when organisms – such as humans – live in groups, communities, or societies that compete with each other, the most strongly cooperative are the ones most likely to survive.

THE JUST SOCIETY

None of this should come as a surprise to anyone except extreme sociopaths – even bullies understand this intuitively, which is why they try to isolate their victims and pick them off one-by-one – but it’s backed up by sophisticated modeling and hard data, not simply soft-hearted, mushy feelings. As Matthieu Ricard has written in his book, Altruism:

According to the mathematical models … groups that contain a majority of altruistic individuals prosper because of the advantages that cooperation and mutual aid bring to the group as a whole, despite the presence of a certain number of selfish individuals, or freeriders, that profit from the altruism of others. The members of this group will thus have more descendants, the majority of whom will exhibit altruistic behavior.

Groups containing a majority of selfish individuals do much less well, because the dominant attitude of “everyone for himself” harms the overall success of the community…. [T]heir group stagnates as a whole, and will thus produce fewer descendants.

In populations and situations where the players are likely to meet again, defection becomes more costly. Reputations can be communicated throughout the entire population, so that fooling one cooperator once can lead to Tit-For-Tat treatment by everyone else. In sum, rather than dominating a society of “chumps” – as aggressive opponents of empathy, humaneness and liberalism believe – a bully by himself, or in some numbers, is shunned and similarly driven out by a cohesively empathetic, human and liberal society.

Ah, but mustn’t we always, consistent with putting others first, turn the other cheek? Well, nope: Even if one is guided by always acting in the interests of others, I think we can specify that, whatever we may decline to do in our own interests, we can always act against those harming others. The humane society as we have defined it, then – where everyone “turns the other cheek” except when (and because) aggressors are harming others – is also, with all respect to John Rawls, how to define the just society.

THE POLARIZED SOCIETY

As we have seen, trusting each other to cooperate leads to better outcomes for all. This is what makes TFT an “evolutionarily stable strategy,” as mentioned earlier. Unfortunately, however, “Always Defect” is also an evolutionarily stable strategy.

How can they both be so? Because, if one or the other becomes established in a population, that strategy will continue to defeat any adopted by some who choose (or, in the case of nature, evolve) to behave otherwise. A population that cooperates will continue cooperatively: If a bully, cheat or sociopath arises, that individual might get away with a few “wins,” but, overall, the population will shut that person down and drive that behavior out. However, if bullying and cheating and “Looking Out For Number One” become established in a population, cooperating – even through TFT – will lose out.

In fact, TFT, despite being the most successful strategy in one-on-one confrontations, has a serious flaw. If playing against a chronic defector, it by its nature becomes a chronic defector, as well, to mirror and punish the bad behavior of its antagonist. This “echo effect” causes an unending string of mutual defections and suboptimal performance for both players: Once the bully prevails, it is not only he, but all, who become bullies and immoral.

How does such a bleak society – where everyone cheats each other and no-one trusts anyone else – become established, especially if bullies and cheats can themselves be defeated? Because, as we know, cheaters can in fact prosper and bullies can prevail by picking off their victims one by one.

It is only if and when the society as a whole – or some significant portion – collectively stand up to bullying, cheating, or threatening that defection cannot gain a foothold and take over a society. Unfortunately, while Tit-For-Tat and Always Defect are evolutionarily stable strategies, Always Cooperate, my preferred moral code, as it turns out, is not. As various games demonstrate, populations are likely to reach a stable balance between aggressors and reluctant aggressors, between heroes and cowards – but will never achieve populations consisting wholly of pacifists or heroes.

So, what happens if, by some chance, defection, alienation, and atomization become sufficiently established in a population? The science of “complexity” – so-called “chaos theory” – has shown that such situations sometimes emerge, like algae blooms, even from previously stable environments in which such eruptions should seem unable to arise.

What you get, in that case, is something like a 50-50 population, where half cooperates internally with each other but defects in an unending “echo” war with the other half, and vice versa. There appears to be, then, no escape from such a polarized society.

Which is where we find ourselves today.

Unless, of course, we each individually, nonetheless, against all logic, persist in pushing beyond Tit-For-Tat and hold to the values of empathy and cooperation, unconditionally.