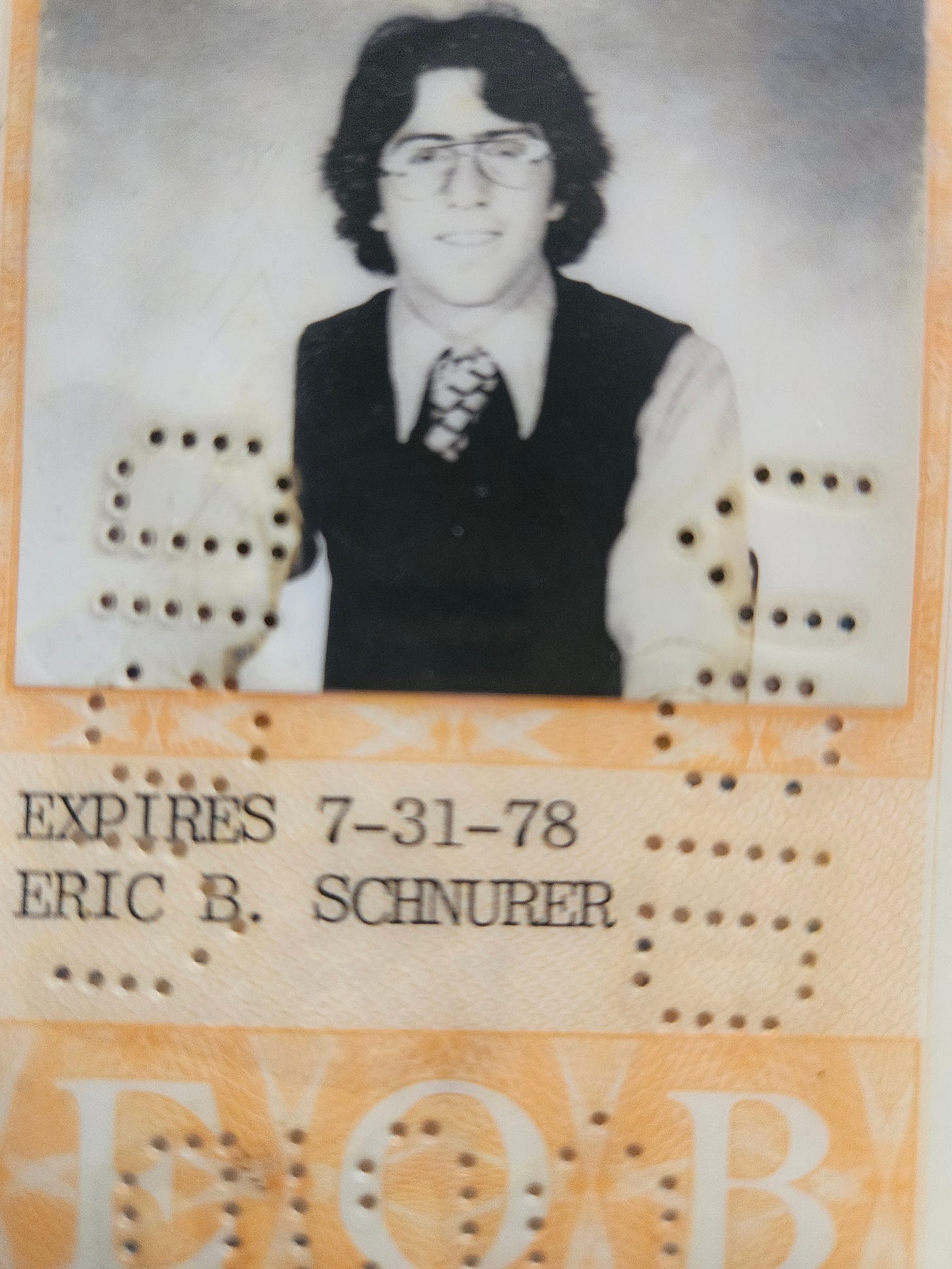

My sophomore summer in college, I worked as an intern in the White House speechwriting office for President Jimmy Carter (very-’70s White House pass, above).

My fellow speechwriting intern was Jon Alter, who went on to become editor of The Washington Monthly, a contributor to Newsweek and MSNBC, and author of – among several books – probably the leading biography of President Carter. I went on to … whatever it is I’ve gone on to.

With his passing, virtually everyone who has some sort of Carter connection has been paying him tribute. My connection is far more tenuous than most. But there is one particular moment in Carter’s presidency – perhaps the most important moment, and, in my view, one of the most important in recent American history – as to which I had a closer view than all but perhaps a handful of Americans. I think it’s worth recounting in some detail, as the nation says goodbye for good not just to Carter but also, with the return of Donald Trump as president, perhaps to everything that Carter’s “American Century” represented.

WHITE HOUSE DAYS

In his recent tribute to Carter here on Substack, Jon noted how he first met the President by shaking hands with him on the White House lawn at that summer’s Fourth of July celebration. I, too, was at that same celebration. But when Carter emerged, virtually the entire assemblage rushed to greet him; unlike Jon, by the time I reached the throng, it was clear I was getting nowhere near him.

As the President neared, though, I thrust my hand blindly into the writhing mass. Carter somehow happened to grab it, and, for some reason, stopped and reached up with his left arm to grasp my hand in both of his. He held it for what seemed an unusually long moment. At the time, it felt like some sort of cosmic connection.

Also unlike Jon, however, who spent a great deal of time with Carter in later years as he worked on his biography, I actually only spoke with the President on one occasion. I forget why, but roughly a decade after he left the White House, I arranged to talk with him over the phone. I just remember him noting that he was headed to Africa and was extremely popular there. “I could probably be elected president of several African countries,” he remarked in his thick, distinctive drawl, and then laughed a very self-conscious, not bitter but ironic, laugh.

I was highly skeptical of Carter when he first ran for president. As Election Day approached, I leaned unhappily to casting my first presidential ballot for a Republican, Gerald Ford. And then came the infamous Playboy interview. I may be the only man ever really to buy Playboy for the interview – and almost certainly the only person to vote for Carter because of it. It was enormously controversial, largely for Carter’s referring to young people “shacking up” (yes, that was scandalous language in 1976) and having “lusted in his heart” after women other than his wife.

What Carter was actually saying, however, was that he understood how some were worried by his overt religiosity, but that his faith also taught him that he – like all people – was imperfect and had sinned (although not very much…), and therefore he believed in tolerating the humanity of others: Because he lived his faith, he was not interested in imposing it on others.

A few months later, I happened, by pure chance, to land a job for my freshman summer as the speechwriter for the Chairman of the Democratic National Committee – not an intern to the speechwriter: The one-and-only speechwriter. I decided that the only summer job that could possibly top that one was to write speeches for the President of the United States – which seemed totally implausible, but, through another series of lucky developments, I found myself interviewing that October with Jim Fallows, the then-29-year-old chief White House speechwriter.

After what has to be the worst interview performance in White House history, Jim asked me if I had any further questions; I had only one and, at that point, figured WTH, so I said, “Can I have the job?” Jim seemed a bit taken aback momentarily, then shrugged and said, “I don’t see why not.” And that’s how I ended up writing speeches for President Carter. (I came back to the White House two summers later, when I graduated from college.)

The summer between my two White House stints, I was hired to write for The Washington Monthly – thanks in part to Fallows, who had worked there as an editor. I wrote two pieces that summer for The Monthly, about editor Charlie Peters’ favorite subject: government waste and inefficiency.

But in between these, one day in early summer, Charlie called me into his office. He said that someone had run into Pat Caddell, President Carter’s pollster, at a party in Georgetown and Caddell had descended into a long rant about how Carter’s presidency was coming off the rails but his top aides wanted only to “circle the wagons,” ride out the attacks, and assume everything would be fine.

Caddell said that he was putting together a lengthy memo on his polling findings and arguments as to why Carter was headed to defeat unless he went in a radically new direction; he planned to “confront” (I was struck by this word) the President with his memo before Carter left for Camp David for July 4th. Charlie assigned me to track down the story and see if we could scoop the world on this impending development – on, in other words, what became the famous “Malaise Speech” – before it was even written.

I was stupefied by this assignment. I wasn’t yet 21, and it wasn’t like I was a close confidant of any of these people. I did what rooting around I could, and found confirmation that Caddell had given the memo to Carter, and Carter had taken it with him to Camp David – leaving in a rather jaunty mood. Then, like the rest of the world, I learned that the President had suddenly cancelled what had been his planned major speech on energy for after the holiday, sequestered himself in Camp David in an apparent funk, and basically shut out the outside world.

As what news that emanated from Camp David grew stranger and stranger, and the rest of the country grew consumed with speculation about what was really going on, I felt I had a pretty good idea.

While my once-in-a-lifetime scoop was swept aside by fevered coverage in all the world’s media – and the specifics of the eventual speech and how it came to be were thoroughly dissected first by Elizabeth Drew in a detailed piece in The New Yorker, in a book by my later editor, Bob Schlesinger, and by Alter in his Carter biography, among others – I remained fascinated by the events surrounding the speech, and became friendly afterward with some of the participants, particularly Caddell and Carter’s vice president, Walter Mondale.

I worked as a speechwriter for Mondale, cutting law school classes for almost an entire semester in favor of his ill-fated 1984 presidential campaign. After his defeat, I got to know Fritz fairly well and would always visit with him whenever I was in DC.

After I wrote my alternate take to Liz Drew’s for my college newspaper, in which Caddell was the hero, and sent it to Pat, we got to know each other reasonably well, having lunches together when I returned the next summer to the White House speechwriting office. We had bonded over the “Malaise” speech, and discussed it in great detail.

That summer, I was able to pour through all the files in the speechwriting office and peruse the various drafts as the speech had come together, read through Carter’s own handwritten comments, and even go through Caddell’s memo to Carter that had set off the whole conflagration. And I talked about it with the speechwriters who had been there, on the inside, drafting the speech and traveling with the President in the days that followed.

So, in many ways, that speech became a central event in my young career and something I came to know very well – and understand viscerally. It speaks to several aspects of where America was at in the 1970’s, and what that meant for where we were headed in the 1980’s – and, I believe, today. Let’s look a little at that.

A MOMENT IN HISTORY

As is generally remarked nowadays, the “Malaise Speech” itself never used the word “malaise.” However, it addressed a general national spiritual crisis that had long been a particular obsession of Caddell’s and that rather obviously had to do with the election of Carter, the nation’s only openly-evangelical president, in the first place.

In the 1970s, the country was dealing with a number of disruptive factors that differed markedly from those of mid-century America. While it’s common to call the present day the most divided that the country has been “since the Civil War,” the Vietnam/Nixon era could mount a serious challenge to that assessment.

The ’70s were a period of backlash against the Civil Rights movement, the extreme cultural liberalism of the ’60s and crumbling of traditional social norms, the American defeat in Vietnam and our disastrous and chaotic final withdrawal (and the resulting sense of an America in decline), and the Nixon Administration’s descent into paranoia, enemies-list vindictiveness, abuse of law enforcement agencies to commit crimes and persecute opponents, and levels of graft unseen since Teapot Dome. In short, it was not very unlike today.

Of particular relevance, the idealistic “Sixties Generation” had given way to what Tom Wolfe pejoratively called the “Me Generation.” Within this general zeitgeist, Caddell loaded up Carter with readings like Christopher Lash’s then-recent The Culture of Narcissism. He believed that his own polling results suggested similar diagnoses: America was suffering from a deep spiritual hollowness after all the events cited above, with people finding no meaning in traditional cultural mainstays like religion, patriotism, or other providers of a sense of common cause or greater good – and placing no faith in virtually any institutions of national life – thus turning to seeking fulfillment solely in very individualized, superficial, materialistic ways.

Of course, even – if not especially – at such times, most people still yearn for a sense of larger meaning that they’re not finding in current institutions and belief structures. Even at such times of spiritual vapidity, there is a desire for some greater calling. It’s hard for many nowadays to recall or imagine, but Jimmy Carter spoke to that desire in his 1976 election, but seemed to lose his way in the presidency.

His popularity plummeted amidst the rising gas prices and “stagflation” – largely out of his direct control – that most Americans were experiencing while Carter, instead, seemed focused (engineer, after all, that he was) on small-bore tasks as manager-in-chief and on highly technical policy issues – particularly energy and climate change – where he is now increasingly hailed as visionary but at the time appeared as disconnected from the daily concerns of real-life Americans.

This all reversed literally overnight with the “Malaise Speech.” To the extent I could follow and guess at the day-to-day developments at Camp David that July, due to the limited heads-up I had as to Cadell’s memo, I could see a man shaken to his core by the foreboding and forbidding message that one of his closest advisors had dropped on him, someone sinking suddenly into self-doubt, and slowly rebuilding a vision of his path forward: first self-reproachful, then in turns spiritually searching, pragmatic and strategic, and finally hopeful and newly self-confident – in fact, ultimately, tragically so.

All of this is echoed in the arc of the eventual speech itself; in fact, it’s worth looking back, decades later, at the opening passages of that speech. After a brief preamble, Carter told us:

It's clear that the true problems of our Nation are much deeper—deeper than gasoline lines or energy shortages, deeper even than inflation or recession. And I realize more than ever that as President I need your help. So, I decided to reach out and listen to the voices of America.Carter then revealed, in surprisingly self-deprecating terms, what these “voices” told him. This is important, as the speech is now largely remembered as slamming everyone else in America for Jimmy Carter’s failings; in fact, quite the opposite was the case.

This from a southern Governor: "Mr. President, you are not leading this Nation– you're just managing the Government."

"You don't see the people enough any more."

"Some of your Cabinet members don't seem loyal. There is not enough discipline among your disciples."

"Don't talk to us about politics or the mechanics of government, but about an understanding of our common good."

"Mr. President, we're in trouble. Talk to us about blood and sweat and tears."

"If you lead, Mr. President, we will follow."This was actually a pretty good diagnosis of the Carter presidency’s problems. But read this list again, and, as in the old children’s IQ test, ask yourself, “Which one does not belong?” The answer became apparent in the next few days, which is its tragedy. But first we must experience the triumph.

Carter – and, in particular, the bulk of his advisors, who abhorred the underlying, essentially theological, thrust of the speech – couldn’t resist weaving in policy wonkisms, especially related to energy. But, in the core of the speech, he unleashed a searing and insightful diagnosis of our society unlike any delivered by a politician previously:

In a nation that was proud of hard work, strong families, close-knit communities, and our faith in God, too many of us now tend to worship self-indulgence and consumption. Human identity is no longer defined by what one does, but by what one owns. But we've discovered that owning things and consuming things does not satisfy our longing for meaning. We've learned that piling up material goods cannot fill the emptiness of lives which have no confidence or purpose.

The symptoms of this crisis of the American spirit are all around us. … As you know, there is a growing disrespect for government and for churches and for schools, the news media, and other institutions. This is not a message of happiness or reassurance, but it is the truth and it is a warning.At this point, a rapt America was paying attention to Carter – perhaps for the first time in his presidency. And Carter then delivered the coup de grâce:

We are at a turning point in our history. There are two paths to choose. One is a path I've warned about tonight, the path that leads to fragmentation and self-interest. Down that road lies a mistaken idea of freedom, the right to grasp for ourselves some advantage over others. That path would be one of constant conflict between narrow interests ending in chaos and immobility. It is a certain route to failure.

All the traditions of our past, all the lessons of our heritage, all the promises of our future point to another path, the path of common purpose and the restoration of American values. That path leads to true freedom for our Nation and ourselves.Contrary to historical memory, this was not a message of defeat and surrender: It was a calling, in the religious sense – and Americans heard it as such. Again contrary to memory, overnight polls showed Carter’s popularity soaring. He clearly had hit a nerve – had, in fact, diagnosed precisely the societal malady, and summoned people to its remedy.

The speechwriter who wrote his addresses the next day, and accompanied the President as he delivered them in (I believe) St. Louis and Detroit, told me that he had never experienced such a welling of emotion as he saw on the hustings with Carter that day; if the President had flown that night directly to Capitol Hill and demanded that a joint session enact his energy plan, he told me, the legislation would have passed within 24 hours. There was a wave of enthusiasm behind Carter that observers at the time had never witnessed with any political figure, as a result of that speech.

And then …. Well, did you find the item that did not belong in Carter’s opening litany of self-criticisms? It was this: “Some of your Cabinet members don't seem loyal. There is not enough discipline among your disciples.” This is the only item in the list that addresses politics and inside-baseball instead of larger metaphysical concerns – and it’s the only one in which Carter is the one being let down, not the rest of us. As it happened, that was one of Carter’s major concerns as he headed off to Camp David that weekend, and it's the one area where Carter let his human-ness get in the way of his humaneness.

In the wake of his sudden surge in popularity, Carter perceived it as the moment to clean house and renew his Administration. So, he fired several Cabinet members. Unfortunately, he chose to do so in the very Nixonian manner of demanding every Cabinet officer’s resignation. That became the story. The public concluded that all of this had been just a shadow-play to reshuffle chairs in Washington. It was the same old politics, and insider games. The Malaise Speech was really just empty hope.

This was unfair – but Carter had done it to himself. His support collapsed immediately. For all intents and purposes, his presidency was over.

What a missed opportunity this represented! Almost exactly one year later, in what I have always conceded was one of the greatest political speeches I have ever heard, Ronald Reagan, in accepting his party’s presidential nomination, told a receptive country that conservation only means running out of energy more slowly, that sacrifice and concern for the collective good are the antithesis of Americanism, and that, essentially – as the movie character Gordon Gekko would sum up the era a few years later – “greed is good.”

Reagan’s acceptance speech constituted a complete and total rejection of not just Carter but also every single sentiment expressed in the Malaise Speech, from the details of energy policy to a commitment to the greater good. And, at that point, the country was ready rapturously to embrace it. In the one presidential debate that fall, Reagan reframed for good the central question in all elections thenceforth as, “Are you better off?” It was indeed a turning point in American history.

WHY THIS SPEAKS TO TODAY

Most of you will hear echoes of the present in everything I wrote above about that moment when the ’70s became the ’80s. Those of you who have read various articles I’ve written in recent years, such as this, will recognize a similar dissection of the “Me-ism” I believe is permeating our culture today. In fact, back in 2016 I wrote repeatedly that Trump’s appeal lay largely in his selfishness – a value, those who shared his sense of aggrievement felt, whose hour had come round at last.

I closed out that year, as Trump prepared to take office the first time, with a piece assessing not just Trump’s election but positions he had taken and appointments he had made during the transition, under the title, “The Age of ‘Who Cares?’.” Eight years later, it reads like it was written yesterday; please go back and read it in full, but it concludes:

The resulting meanness and self-concern of the current moment are understandable. The world is undergoing a series of changes that won't be fully understood for decades, but are clearly disrupting the economic, cultural and geopolitical arrangements most people have been used to all their lives. That meanness and self-concern, though, is nonetheless corrosive. We can survive economic transitions from agrarian to industrial, and from feudal to capitalist, to whatever comes next; we can survive polities that transform from principalities to nation-states to empires and back. But a world where no one cares about anything other than themselves is one that few survive.Trump is generally viewed as sui generis. I don’t believe he is. He is the output, not the author, of our times, and in that merely the apotheosis of the strand of our psyche – the one that has given up hope for any cause greater than ourselves in our institutions, our culture, or our society and instead turned inward for meaning and outward merely for objects of consumption, material or human – against which Carter warned.

This is a choice we have faced before and must again in the years ahead. It is why this newsletter, and my book-in-progress, are called The Greater Good (I also started a conference and related efforts under this name): Those who wish the country to choose a road as yet not taken ultimately must present and articulate a credible alternative path … and then remain unrelentingly and unswervingly true to it.

Like Jimmy Carter, being human, we can perhaps allow ourselves momentary lapses in constancy and purity of purpose – although not very much.

Thanks for reading,

Well done and interesting.

Excellent piece, Eric. My one quibble might be with the weight you assign the disloyalty and dysfunction of Carter's staff as the main reason for the preciptous drop in Carter's popularity over the last year and a half of his presidency. Found myself nodding in agreement with the rest of your analysis, and loved your diagnosis of Reagan's widespread appeal. Looking forward to reading (and buying!) the book. Keep the inightful articles coming!